I have a particular tic when I do interviews. While talking to the artist, often a musician, it will have registered that I’m looking at a regular person. I’ll try to align that ordinary person before me with the extraordinary voice, or lyrics or performance that is his or her art. Then I blurt out, as if part of a two decade-long research project in the creative process: “How do you do it?” I’ve posed the question to all kinds of artists from teen popsters with great voices to Sinead O’Connor, Wynton Marsalis, Chaka Khan, Jonathan Biss and Johnny Rotten. How could they explain? There is always a spectacular gap between what can be said and what happens in the art. Great art dwarfs the individual artist. The art is better than their personal lives, politics and attempts to explain themselves. Like the white space in a poem, it happens in the in-between.

I have a particular tic when I do interviews. While talking to the artist, often a musician, it will have registered that I’m looking at a regular person. I’ll try to align that ordinary person before me with the extraordinary voice, or lyrics or performance that is his or her art. Then I blurt out, as if part of a two decade-long research project in the creative process: “How do you do it?” I’ve posed the question to all kinds of artists from teen popsters with great voices to Sinead O’Connor, Wynton Marsalis, Chaka Khan, Jonathan Biss and Johnny Rotten. How could they explain? There is always a spectacular gap between what can be said and what happens in the art. Great art dwarfs the individual artist. The art is better than their personal lives, politics and attempts to explain themselves. Like the white space in a poem, it happens in the in-between.

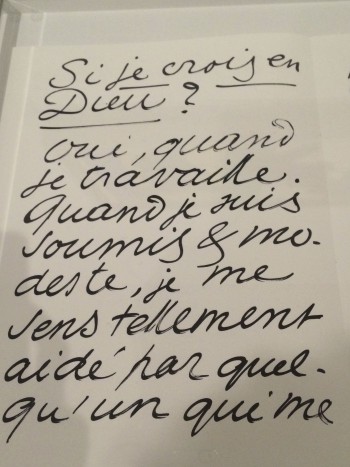

I was fascinated when reading Matisse’s riffs in his artist book Jazz, so calligraphically written and (seemingly) spontaneously composed with wit and candor. He asks rhetorically, “Do I believe in God?” His answer: “Yes, when I’m working.” He goes on: “When I’m open (when I submit) and I’m humble, I feel enormously aided by someone who helps me do things way beyond my capabilities.” Matisse admits to not knowing how to respond: the process is so mysterious and opaque to rational understanding, he imagines that someone is pulling a magic trick. He doesn’t know how to respond in kind: he can’t. So he feels like an ingrate.

Matisse writes that hate is a parasite that devours everything, and that love is the buoyant medium that keeps the artist afloat. Clio, my fictional character of Clio’s Mobile Home, would wholeheartedly agree. When she’s feeling creative, she recognizes a quivering attentiveness to a whole field of perspectives and voices that might be male or female, from the past or present. This openness is a commitment; and the commitment to stay open keeps her creativity in constant rotation. It’s not hers to use up. It might not be hers at all.