I might have expected a country as old as Bulgaria, a culture that has seen it all, to accept the inevitable compromises of war. After all, as cynics say, only the naive fight for “how it should be.” Yet during World War II Bulgaria fought for and lived its ideals – within parameters. Traveling to Sofia and its second city, Plovdiv, I was surprised at the story of how Bulgaria stood up for its Jews.

I might have expected a country as old as Bulgaria, a culture that has seen it all, to accept the inevitable compromises of war. After all, as cynics say, only the naive fight for “how it should be.” Yet during World War II Bulgaria fought for and lived its ideals – within parameters. Traveling to Sofia and its second city, Plovdiv, I was surprised at the story of how Bulgaria stood up for its Jews.

Surprising, first, because the country allied with the Nazis. That would seem to signal the demise of the Jews who’d had a presence since ancient times, and had settled in the thousands after the Spanish Inquisition. If Bulgaria feared the crushing regional power of Germany, it would seem to be the end of story.

Indeed, Germany agitated for them to adopt their laws of cleansing government, schools, residential places. The minimal changes in workplace was unacceptable, so Germany sent Eichmann to teach them to harsh methods for their “a Jewish Problem.” They didn’t seem to think they had one. People felt sorry for the underdogs. Officials tried to arrange for shiploads of Jews to cross the Black Sea to Palestine. Britain shamefully refused entry and that arena was closed.

Running out of options, on March 9-10, 1943 Bulgaria ordered its Jews to be removed from their homes and taken to collection points to be deported. What happened was a national refusal. Farmers in the countryside threatened that if Jews were put on trains, they would block the tracks with their bodies. All members of parliament argued that such actions violated the country’s guaranteed civil rights. The Orthodox Church vigorously stood up for the life and rights of the Jews. The King, himself opposed the action, cancelled it, and the Jews returned to their homes.

In Plovdiv, I came upon a monument: To all who helped to save us on 10 March, 1943, from the grateful Jewish community of Plovdiv.

And according to most records, the 48,000 Jews of the country were saved. In disgust, the Germans wrote that “Bulgarians have lived too long with peoples, like Armenians and Greeks, and Gypsies, to appreciate the Jewish problem.”

But on the other hand, Bulgaria sacrificed thousands of Jews whom, they claimed, were out of their control, in German-controlled Macedonia and Southern Thrace. All died at Treblinka.

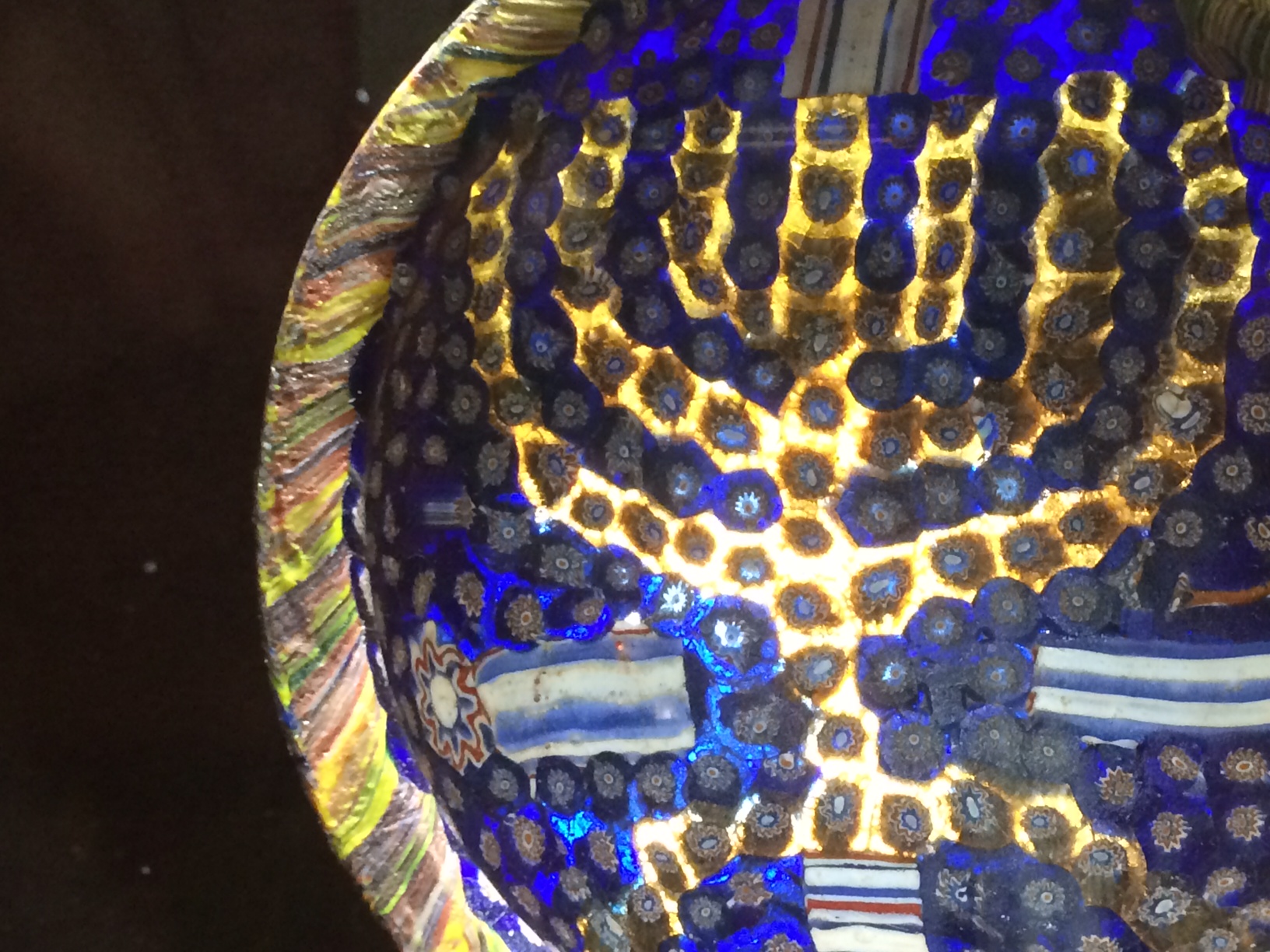

In Sofia, the small synagogue stands in the vicinity of a mosque and the main Orthodox church. The small domed synagogue in Plovdiv is fading. The largest presence of Bulgarian Jews is now in Israel, as most of the community emigrated after the war. From there and abroad, historians and intellectuals have written their stories of common – and uncommon – decency.

This is an extraordinary piece. The management of tone confirms the complexity and subtlety of the facts. The mix of personal and historical is perfectly proportioned. It is tempting to say it is poetic prose but that obscures the specificity of the accomplishment.